(This blog post is written in personal tone, but relates to our work at GitHub Next and may be moved to https://githubnext.com in future. A huge thank you to Peli de Halleux, Joe Zhou, Eddie Aftandilian, Russell Horton, Idan Gazit and many others at GitHub Next, and the GitHub platform leadership of Mario Rodriguez. I’m also grateful to my colleagues Jie Zhang and Lukas Twist at Kings College London for discussions about this work)

I previously introduced GitHub Agentic Workflows, an experimental agentic framework we’re working on at GitHub Next. This framework is for exploring proactive, automated, event-driven agentic behaviours in GitHub repositories, running safely in GitHub Actions. The focus is on Continuous AI workloads, in a similar way to how GitHub Actions YML is focused on CI/CD workloads.

Two of the most fascinating and promising application areas for semi-automatic software engineering are Continuous Test Coverage Improvement and Continuous Performance Improvement. I wrote a taster about the first of these in this post. Today I want to talk a bit about the challenges and opportunities of Continuous Performance Improvement.

Personally I believe generic, heterogeneous Continuous Performance Improvement is one of The Grand Challenges ahead for the software industry. It is something that just a year ago I wouldn’t really have believed was remotely possible, but is now, in some cases, practical. And yet in other cases it feels extremely far off (more on that below). This hints at how agentic software engineering is in a nascent phase. We are witnessing a shift from

- manual coding to

- assisted programming (completions) to

- task-oriented programming (vibe coding) to

- semi-automatic engineering (event triggered agentics)

This shift opens the door to entirely new kinds of work, and new kinds of engineering. I believe that, in 2 to 5 years, every CS faculty will (or should) be having a course on semi-automatic agentic software engineering, in both individual and team settings.

A Definition

A definition: Continuous Performance Improvement involves an automated agent or coding algorithm running repeatedly over a repository researching, planning, preparing, measuring, coding, tuning, re-measuring and testing while pursuing overall performance goals aligned with the higher goals of the software and its maintainers. I will use the term Semi-automatic Performance Engineering to mean the same thing, but where there are one or more humans in the loop reviewing, charting and guiding progress of the automation – whether through initial goal-setting, conversational chat, making comments on plans, reviewing and merging pull requests, double-checking performance results, doing coding.

Already we see that this is a serious business, involving repo-centric behaviours that go well beyond vibe-coding’s “fix this bug” or “implement this feature” (which is of course, already amazing).

Tackling Heterogeneity

Now don’t get me wrong, performance engineering is stunningly hard. Performance is not just one goal, but is often a whole matrix of overlapping concerns. Usually we break it down into CPU, Network, Storage, with overall goals like throughput and latency or Spending Less Money (e.g. operations) or Making More Money (e.g. high frequency trading) or Making the User Happy (responsive UIs). CPU performance alone is a huge topic – cache misses, cache sizes, vectorization, memory hierarchies, alignment, garbage collection and tens of other major topics that involve deep knowledge and expertise. I recall watching amazing engineers work for months on the performance of developer tools alone: compilers, JITs, GCs, editors, language services, libraries. I’ve done a little in the performance of web applications, which is a vast area of its own. Cloud performance, network performance – it’s all huge.

What this means is that performance engineering as a whole is very, very heterogeneous. Every major piece of software is both a cornucopia of delight and a vast swamp of complexity and likely an outrage of horrors when it comes to performance engineering. I’ve heard story after story of the most ridiculous performance bugs, ridiculous architectures that cause them, and monumental, epic engineering achievements to overcome these. None of this will stop any time soon: amongst all the tweets, hype, venture capital, spectacular failures and glitzy demos of the tech industry, performance engineers are a vastly under-appreciated discipline. Further, they need help, and they need tools that will make them 100x more productive, because frankly there is so much serious performance engineering work to be done across the industry that no multiplier would ever be enough. Almost every major piece of software is a cratered wreck of effort after effort to do good performance engineering – in hidden directories you’ll find the magic scripts to run long forgotten critical major benchmark suites. The more productive, consistent, repeatable we can make performance engineering, the better for everyone.

So the grand challenge is this: a generic agent that can walk up to any piece of software, anywhere, cooperatively formulate and clarify useful performance goals, analyze appropriate performance data, make appropriate performance measurements, propose useful contributions, and self-improve from its work, under human guidance. That is, a performance agent that can navigate the vast ambiguity and heterogeneity of software in the wild, and the heterogeneity of performance engineering even within a single large codebase.

Navigating that heterogeneity is of particular interest to two main providers in the industry: general-purpose model makers and software collaboration platforms. The former because they have the big generic hammers and naturally look for big, generic applications of those. The latter because platforms like GitHub are home to a breadth of software of the most heterogeneous kinds. At GitHub, it’s of particular interest to work out what performance improvement might look like from a highly heterogeneous starting point. At GitHub, we don’t know if an agent will be applied to a single python file, or 20 x86 assembly code files for GPU optimization, or a standard software library project in Java, Python or .NET, or a monorepo with 500 sub-projects.

Automated performance engineering is a long-standing and active research area. What interests me about agentic performance engineering specifically is the incredible ability of LLMs to navigate the heterogenity and peculiarities of the space:

- Coding agents can realistically investigate and cooperatively shape performance goals in any of a vast variety of repositories

- Coding agents can perform long-range planning and problem decomposition in the context of a specific repository

- Coding agents can effectively invoke and use nearly all command-line micro-benchmarking, performance measurement and analysis tools available, to a level of detail often beyond humans

- Coding agents can analyze, read and make nuanced judgements based on the broad range of reports that performance analysis tools produce

- Coding agents can easily discover and be instructed to integrate build and test passes to help ensure quality.

While algorithmic approaches can be used to detect coding patterns, or deal with specific sub-problems in code improvement, the sheer heterogeneity of software on GitHub means a truly broad-spectrum tool must start with a different approach. We need to start with high-level research, planning, tool discovery and goal-setting, in order to specialize performance engineering to the peculiarities of the software in question, before adopting iterative improvement.

An Example Approach

To make things concrete, for this post I’ll be talking about one modest realization of Semi-automatic Performance Engineering, which is the Daily Perf Improver workflow sample of The Agentics sample pack of GitHub Agentic Workflows. This is not a production ready sample, but it is possible to use it well if carefully supervised and you become Learned in the Magic Arts. [ caveat: These magic arts include many mundane things! ]

The heterogeneity and complexity of performance engineering means that the aim of Daily Perf Improver is to achieve what is clearly impossible: to have “the AI” – that is, modern coding agents – walk up to arbitrary software repositories and perform realistic and useful performance work. This is so clearly impossible in general, that you can stop reading here if you like. Except, sometimes it works. For small-scale software. The impossible is gradually revealing itself to be just partially tractable.

First, let me explain how Daily Perf Improver works. Or if you like just read the agentic description!

First, the workflow uses a three-step self-improvement, “fit-to-repo” process:

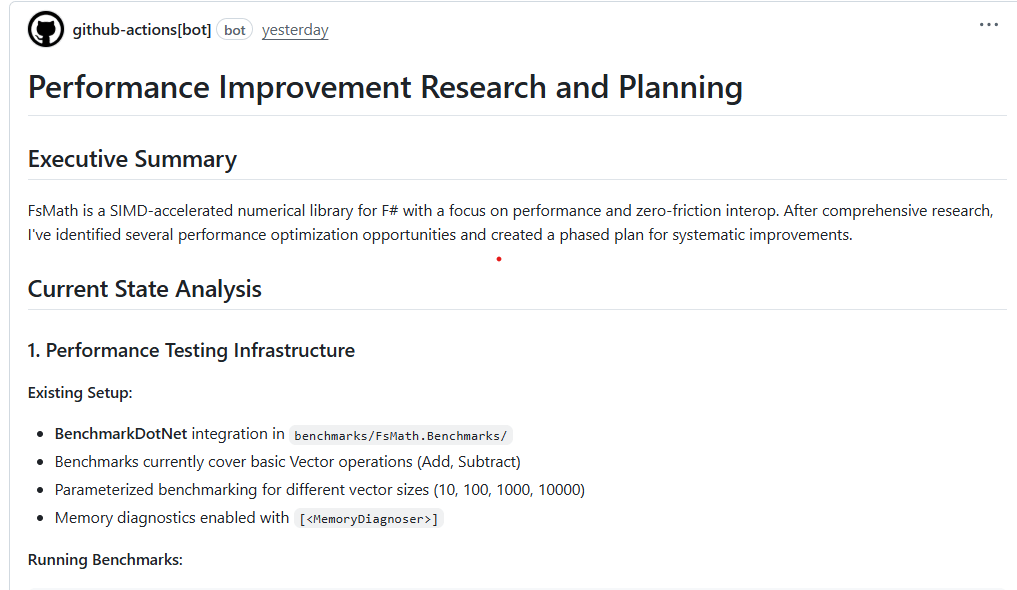

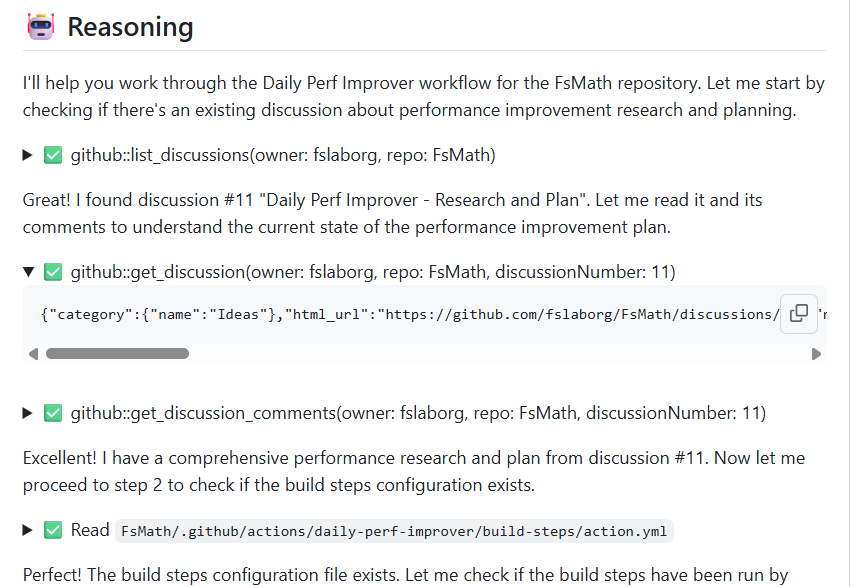

If you read the workflow, you can see those phases clearly laid out. To see this in action, here is the planning run of using Daily Perf Improver on the FsMath library, an open source Math library from the F# community. The logs show the reasoning, tool uses and investigations of the coding agent. The resulting plan is then stored as a GitHub Discussion, which will be referenced by later iterations.

Fit to Repo: From Potential to Actuality

We use a three-step fit-to-repo in order to begin to tackle the impossible: performance engineering is so heterogeneous, that nothing is possible in general, and to achieve something specific you need very detailed notes about what you’re trying to achieve and how to do it. AI agents need this as much as anyone.

Secondly, performance engineering must be repeatable, reliable, measurable. This has many challenges, and in this context we’re using cloud-hosted VMs in GitHub Actions as our runners. This has many downsides. But for now let’s just let that slide and assume that the measurements that we take are sufficiently reliable.

The need for repeatability is one reason why we do Build step inference – which is all about “setting the coding agent up for engineering success”. That is, in this step the agent works out how to do basic taks such as build the software and run micro-benchmarks.

We do 3-phase “Fit to Repo” partly because we’re doing a mix of “soft fit” learning and “hard fit” build step inference. The workflow is using the ability of GitHub Agentic Workflows to have a mix of regular GitHub Actions steps and then a more subjective agentic phase.

“Fit to Repo” is a form of an Intent/Actualization Toolchain, and many of the core principles apply equally here. It’s also an example of Bora’s Law in practice: Intelligence scales with constraints (“fit”) not compute.

Making it Real

To install this workflow in a repository I use

# Install the 'gh aw' extension

gh extension install githubnext/gh-aw

# Add the perf improver as a GitHub Action via a PR

gh aw add githubnext/agentics/daily-perf-improver --prYou then have to choose a coding agent, add a secret and add engine: claude or engine: codex to the workflow if you’re not using the default, which is Copilot CLI. After you accept the PR you can do

# Trigger a run of the workflow immediately

gh aw run daily-perf-improverAlternatively you can do a one-off trial of the planning stage of the workflow by

# Trial the first planning stage of the workflow

gh aw trial githubnext/agentics/daily-perf-improver \

--logical-repo OWNER/REPO which will create by default a private personal repo to run the agentic trial in. This must be used with care (read the caveats very carefully), and should not be used over private or internal repositories. It also only runs the initial planning phase, which while interesting may not be what you’re after.

And what happens? Well, first, these things take a while. What will happen is a GitHub Action workflow run is triggered, e.g.

🔨 Running workflow: daily-perf-improver

Successfully triggered workflow: daily-perf-improver.lock.yml

🔗 View workflow run: https://github.com/fslaborg/FsMath/actions/runs/18434400666After that workflow run completes, in about 5 minutes, you will get an initial performance research and planning report . The plan will look something like this:

After you read and assess that report, you can either wait a day for the next automated run of the performance improver. Or, being impatient, you can run again:

# Trigger the 2nd run of the workflow immediately

gh aw run daily-perf-improverThat’s simple! After this run completes, the second phases of the work is done. A new pull request will appear, called Daily Perf Improver – Updates to complete configuration. This contains the results of Build Step Inference – essentially following these instructions (and topically related to another project at next called Discovery Agent). The aim here is to discover a repeatable, reliable engineering basis for further automated engineering work, and to get that reviewd and approved by the human overlord.

Finally, the third run – good things come in threes!

# Trigger the 3rd run of the workflow immediately

gh aw run daily-perf-improverThis run may take a bit longer – maybe 10 minutes. After this, all going well, you will get your first PR contributed.

NOTE: You will have to close/reopen the pull request to trigger CI.

And this is, of course, where you start to find out whether semi-automatic perf engineering in your repo is possible, potential or complete delusion. More on that below.

If you’re happy with what you’re getting, and you want to burn the house down, we have you covered:

# Trigger repeated runs, every 15min

gh aw run daily-perf-improver --repeat 900With that you will get a steady stream of PRs. Whether they are good or not, that will be up to you. After each the workflow leaves a note on the planning discussion, as a form of agentic memory, it should in theory avoid duplicate work.

The Possible

To cut to the chase: if you have

- a relatively well-engineered, standalone piece of software like a library, and

- have clear performance goals, and

- have good performance engineering tools available in your ecosystem, and

- have performance goals where VMs can be a suitable approximate environment for doing performance tuning, and

- your build/test/microbenchmark times are ~2min or less, and

- you have some money or an AI subscription to burn

then semi-automatic performance engineering may already be possible on your software today.

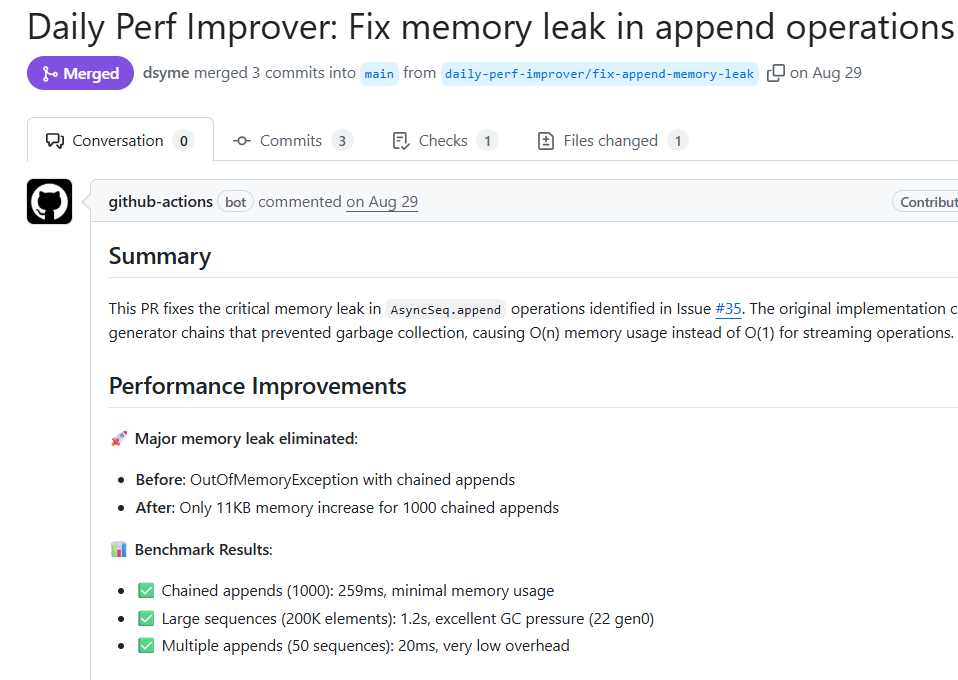

To give an example: a month ago I pointed an earlier version of Daily Perf Improver at the FSharp.Control.AsyncSeq library. This was one of the first language-integrated asynchronous sequence programming libraries, part of F#’s role in the history of the invention of language-integrated asynchronous programming. It is a good library, but has emphasised stability, not performance. The 7 pull requests from Daily Perf Improver were all accepted

- One was the self-configuration build inference

- During research, the coding agent had searched issues and found a major performance bug that had been closed unfixed, and correctly fixed the issue

- The coding agent then proceeded to optimize basic routines (e.g. mapAsync) in the library one by one, using the BechmarkDotnet library to write and run micro-benchmarks.

- The optimizations were correct and existing tests gave excellent coverage.

This indicates that Semi-automatic Performance Engineering is “real” – some of the time!

To get a feeling for what the coding agent is actually doing, the logs are available and parsed, e.g.

The Potential

Since that early experiment in August, we have done further applications of Semi-automatic Performance Engineering. As indicated above, there is a huge amount to learn in this space, and while some simple libraries are within reach, much is out of reach.

I won’t cover the full details here, but we have had enough successes and enough “meh” that I will say “this place has potential”.

- We have applied this particular improver to a fork of a community C++ math library called LibRapid.

- While we didn’t merge these results, numerous bug fixes were found, some huge performance gains, some potential proposed improvements, and some possibly delusional proposals.

- We have also applied this to Python and Rust libraries, and other F# community libraries including FsMath (mentioned above). These again show the same variation in results.

The Delusional

A few weeks ago we got over ambitious: we tried these on the Z3 Theorem Prover, a 250,000 line C++ codebase monster. This is one of the most sophisticated logic-algorithmic pieces of software ever written, a truly vast achievement by Microsoft Research’s Nikolaj Bjorner and others, a work so momentous it deserved a prize all of its own.

That experiment didn’t go so well: almost none of the PRs were accepted. but we learned a lot:

- It is important to build confidence with all the repo maintainers – not just the one person eager person willing to let you trial something

- It is very important to have a way to trial the workflow before installing it in the repo and inflicting it on the maintainers and community.

- The repo is a shared space, and the use of AI agentics is controversial and will result in some inevitable AI Slop.

- Automated agentic perf engineering in a complex C++ codebase is very very hard and we achieved no real success with this in Z3.

- One PR remains open, the rest closed as AI Slop.

- The PRs generated were plausible but no really reliable evidence of perf improvement was gathered by the coding agents.

- Build timeouts were common because, well, C++.

To give a flavour of what the proposed PRs themselves were like

- GOOD: The coding agent knew enough about this kind of software to look in the right places. For example, the coding agent focused on hash functions and hash tables.

- MEH: The coding agent really, really likes to fantasise about improving cache alignment and prefetching in C++ code. Several PRs were in this topic.

- MEH: The coding agent made a brave, valiant attempt to implement a machine-learning optimized variable ordering in the Z3 SAT Solver. As Nikolaj Bjorner said: this is is the holy grail – this is cutting edge. The coding agent reported fantastical gains for this, but these were simply hallucinated. The coding agent is not wrong: amazing gains are possible through this technique. And maybe the draft could inspire a human to work further in this area. Or maybe with a few iterations the coding agent would have succeeded. But the PR itself was useless – while the code built, the numbers simply didn’t materialise.

This points to the frustrations of this work. We don’t just need hallucination. We need real, verifiable, definite improvements.

The Centrality of C++

C++ is where most of the most performance critical software in the world is located. Cracking semi-automatic performance engineering for C++ codebases will require co-investment by both human team and AI coding agents. The AI coding agents must be “set up for success”, just as human performance engineers are. This means human overlords must be willing to plan, monitor and tolerate days or weeks of AI investment in improving the performance engineering flows in the repository itself.

Show Me the Numbers

Why did semi-automatic performance engineering work in some repos and not others? It is not just about “size” or “complexity”.

At the centre of good performance engineering is measurement. The basic steps in the 3rd phase of “do some actual work” for the coding agent are all about measurement: run micro-benchmarks, take before/after figures, look at a variety of workloads etc.

One of the huge challenges of semi-automatic performance engineering is to get AI models to actually, definitely, reliably take these measurements. If you look at where we had success, it was about micro-benchmarking. This is practical to do within the time-constraints typically involved: say 20min timeouts on an Actions VM.

Where things got more challenging were with the long C++ build times and very difficult micro-benchmarking in the Z3 repository. When build times are 15min, or there are 100s of potential C++ configuration flags, the AI models tend to find performance engineering as hard as humans. If you look carefully through the coding agent logs of the Z3 runs, you will see timeout after timeout in building code and taking measurements. This means any supposed “figures” in the performance results are likely to be hallucinated or fabricated. It is surprisingly difficult to get the coding agents to be “honest” about what has or hasn’t been achieved.

This indicates that adding a critique stage to the Performance Improver model will be absolutely essential in future work. Since the Z3 experiments we have added some “honesty appraisal” to the basic step (3) of the workflow, and that can be seen in practice here. However this is not enough. An iterative critique stage must be very demanding, requiring absolute verifiable proof that the performance measurements have been made and improvements observed.

Summary

In this post I have introduced Semi-automatic Performance Engineering as a form of Continuous AI. This can be partnered with other “Code Improvement” automated engineering such as Test Coverage Improvement of Code Duplication Detection or a myriad of other potential improvements. I’ve shown one demonstrator for Semi-automatic Performance Engineering, based on coding agents (Claude Code, Codex, Copilot CLI), the GitHub platform, GitHub Actions and GitHub Agentic Workflows.

One of the reasons I’m interested in this field is that I am aware of the truly vast levels of technical debt that exist across the software industry: the Trillion Line Hangover from the coding binge of the last 70 years. While we can’t pay off all that debt, it is possible that guided automation can make huge strides in making software more performant, better documented, better tested and more pleasant for future generations.