[ notes made for a panel at AI Native Dev podcast ]

LLMs and Coding Agents affect all aspects of software engineering – documentation, specifications, tasks, intent, summaries, code generation, methodology, testing and many more – all are being tumbled about and turned inside out, by the arrival of LLMs on the scene.

My usual habit is to try to “make sense of it all”. That is, I search for ways of thinking about what’s going on, for mental models that can act as a kind of “Stable Chart” through times of change.

Some people don’t do this: they might instead look for “North Stars” – passionately held ideals that inspire and drive. While I have had my moments as a zealot in the past, most the time I honestly just want a chart. I want to make sense of why System A is the way it is, how System B is different and to understand the consequences. A basis to make careful, rational, well-considered decisions, to then decide, commit and act.

From Intent to Execution

In this blog post I’ll discuss some of my mental charts of the interplay between specifications, agents and tools. Some of it will be a bit abstract, but that’s the nature of these things. I’ve written previously about What Kind of Programming is Natural Language Programming, and Dijkstra’s Ghost, and a particular idea in Spec-driven programming called Ephemeral Specifications or Extract, Edit, Apply. In this post I want to explore a different concept which I call Intent/Actualisation Toolchains. That is, toolchains that take in “intent” (e.g. a loose specification, or a list of requirements, or a chat session), and end up “actualising” it – as elaborated specification, or generating code, or executing it – that is, making the potential in that intent real.

To set the scene, let’s consider SpecLang, a prototype system from GitHub in 2023 that attempted to make modular specifications “primary”, and included a non-deterministic compiler that used LLMs to convert these specifications to code. A similar tool today is Codeplain. The simplest form of these systems can be summarised with the simple diagram “Spec —> Code”. The spec is the intent, the code is the actualisation, and a coding agent is a compiler.

Spec ➡️ Code

At 10,000 feet up, this is my mental model of SpecLang. It is a good starting point because it was in some ways the simplest: Words In, Code Out. Of course, a coding agent does the “compilation”. All through this post, I’ll be assuming coding agents are doing the amazing things they do, whenever the ➡️ are involved.

Likewise we can consider the “App Dev Toolchains” (GitHub Spark, Lovable, v0.dev, Firebase Studio, the technology behind Cogna, and many more). There are many of these and they all differ a bit, but essentially they all start with some kind of app description (a very loose specification or requirements), and then elaborate that in some way (to a more detailed specification – for example GitHub Spark writes a PRD – a Product Requirements Document), and then generate code. My mental model for the intiial generation phase of these tools is roughly

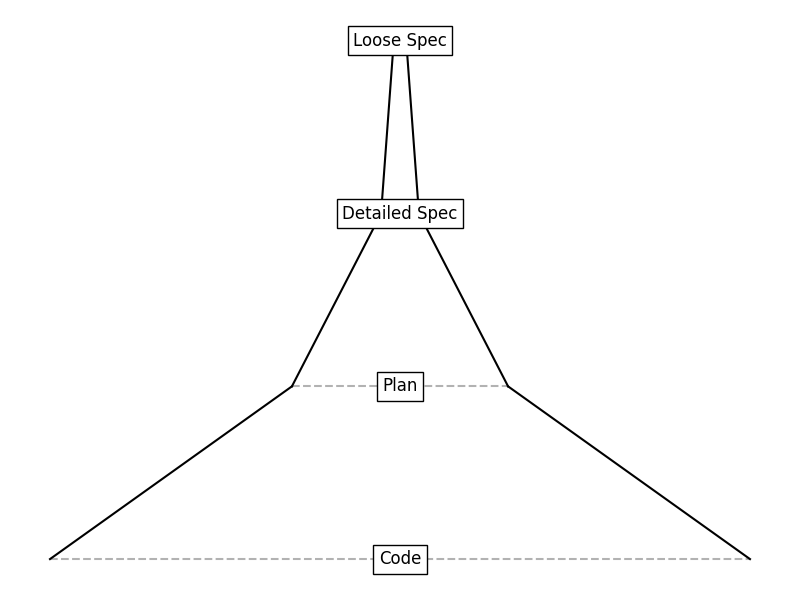

Loose Spec ➡️ Detailed Spec ➡️ Code

The details differ, and these tools generally support iterative development, but the above is the basic operation of these tools, from 10,000 feet up. Again, these are about Intent to Code. The “Loose Spec” is pure user intent – user input – the detailed spec is “elaborated”, the plan “breaks things down” into steps/tasks/phases/components, and then code is generated.

Likewise we can consider Copilot Workspace, a prototype system from GitHub Next in 2023 that I worked on and which pioneered the whole idea of task-oriented programming, an early form of vibe coding. When used in its purely generative mode, this tool used a similar hierarchy of elaboration and actualisation:

Loose Spec ➡️ Before/After Detailed Spec ➡️ Plan ➡️ Code

This predates the App Dev toolchains, and directly influenced some of them. It had a few minor differences in the texture of the intermediate spec, the nature of planning, and lacked a later “validation” phase. But again it was intent in, then elaboration, then code.

Similarly we can consider the basic structure behind Spec Kit, a recent arrival in the area of Spec-driven programming. This tool has a layered hierarchy of intent and actualisation. This adds a new member to the “spec” family called “Constitution” and is roughly characterized as

Constitution | Spec ➡️ Plan ➡️ Tasks ➡️ Code

A CLI toolchain helps you elaborate and expand the spec, and also divide-and-conquer on it. The Constitution is meant to hold steady no matter how many attempts you make at the Spec (🇺🇸 got that?)

To complete the picture, we should not forget that Code is not the end of the story. Code is just one step before true Actuality – that is, Execution, giving, say:

Spec ➡️ Code ➡️ Execution

Finally, in some kinds of natural language programming a Code stage is not needed at all – you can simply interpret and actualize the spec directly as a program, e.g. by using a “natural language interpreter” such as coding agents like Claude Code or Codex. embracing “full agentic execution”. I picture this as follows:

Spec ➡️ Execution

or

Intent ➡️ Actualisation

This is Natural Language Programming in its purest form: words in, execution out. It’s an expensive way to execute and I’ve argued elsewhere it is best seen as a form of constraint programming. But it’s a simple and real thing that’s part of the possible range of toolchains in this space.

To summarize – any kind of toolchain involving “specs” implies the toolchain takes some position on Intent, Elaboration and Actualisation – which can also be seen as a Hierarchy of Actualisation – where possibility/intent/ambiguity becomes actuality/reality/detail. I also sometimes picture this hierarchy like this, as expanding detail at each stage. This expansion can also be understood as a “reduction in ambiguity” or a “narrowing of the possible solution space”.

TLDR: The design space of tools that actualise Intent is, well, a design space.

A Philosophical Aside

The idea of a duality between potentiality and actuality is as old as the hills – a basic philosophical principle that goes back to Aristotle. At one extreme we have pure potential and the other we have full actuality.

There are other philosophical systems where potential, actuality and change appear including Process Philosophy (Whitehead) and liberal theological systems such as Paul Tillich’s (c.f. Systematic Theology Part 3).

So these software development toolchains and methodologies are connected to long standing ways of thinking about the world. I’m a big believer that the more we use words and natural language as technical devices in software engineering, the more relevant insights from the humanities will become. And that every computer science student should be studying at lease one humanties course, given the linguistic skills needed in this new world.

TLDR: Don’t diss the humanities

Change and Reconciliation

In Intent/Actualisation Toolchains, time usually involves filling in the phases left-to-right: mirroring the classic waterfall model of software development. I’ll represent time by sequences down the page:

Loose Spec

Loose Spec ➡️ Detailed Spec

Loose Spec ➡️ Detailed Spec ➡️ Code

…

However, there can also be other change over time. For example, in most of these systems the spec can change:

Loose Spec ➡️ Detailed Spec➡️ Code

Loose Spec’ ➡️ ???

The inevitability of change is fundamental. The first question you should ask of any Intent/Actualisation Toolchain is how does it handle change?

When change happens, there is a disturbance in the force. Some kind of reconciliation is needed – the change in Loose Spec must be “applied” or “reconciled”. Usually this is done by “pushing the change down the line” in a kind of commuting diagram, e.g.

Loose Spec ➡️ Detailed Spec ➡️ Code

…..⬇️…………………….. ⬇️ ………………..⬇️

Loose Spec’ ➡️ Detailed Spec’ ➡️ Code’

That is, the updated Detailed Spec and Code are computed with respect to the previous state. This means that, in practice, most of these toolchains operate over a paired tuple of artefacts, in this case (Loose Spec, Detailed Spec, Code) and all three evolve together under change. People might say that the Detailed Spec and Code are “cached”. The step by step progress of the system under change is to pair both Spec and Code in lockstep:

(Loose Spec, Detailed Spec, Code)

…….⬇️

(Loose Spec’, Detailed Spec’, Code’)

…….⬇️

(Loose Spec”, Detailed Spec”, Code”)

This is basically an incremental compiler with cached intermediates. This has pros and cons.

The first problem is that, as tool maker, you will be tempted to make the Detailed Spec and Code user-observable and editable. For example, the Detailed Spec and Code may contain generated mistakes or be stuck in some kind of local minimum where they are like smelly garbage polluting the state of the system. In general this kind of “hidden state” is not great, and a swathe of tests must be generated to bank the correct behaviour of the overall app. However those tests can also be a burden as the system progresses forward.

The second problem is that, as a user, when rely on “the Detailed Spec and Code being cached” then you’re probably tying the application to the toolchain. This is a form of lock-in. It may not matter, and it may be possible to later “detach” the code from the specs (see below)

The third problem is that the evaluation of toolchains that support change propagation is not simple (e.g. prompt evals). Even deciding what is “true intent” in the incremental situation is hard, as the entire history of changes to the Loose Spec can be seen as part of the declaration of intent, and if you’ve let the user look at the code then even that intent may be inexplicable without knowledge of the code and its history at each point (“revert the workaround in file X to three stages back”). This means it’s hard to determine what to even compare to for evals and benchmarking. Regeneration-from-scratch is needed in some cases where Spec and Spec’ are so divergent that it makes no sense to apply changes to the derived Code incrementally. In practice most toolchains “make it up as they go along” with a mishmash of “propagating deltas of change” , human guidance and “regenerate from scratch”.

The fourth problem is that some of these systems allow changes in the middle of the hierarchy. For example, it may be possible to edit the Detailed Spec directly:

Loose Spec ➡️ Detailed Spec ➡️ Code

…………………………….⬇️

……………………. Detailed Spec’

At this point the toolchain must decide whether to support “forward propagation” of change to the code (extracting change in Code from the indicated intent of the edit in Detailed Spec), and “back propagation” of change (determining if the Loose Spec should change).

In practice toolchains don’t always do a great job on this kind of reconciliation. Overall what I call the burden of actualisation begins to become apparent. This is a fundamental lesson of Intent/Actualisation Toolchains: the more you actualise intent, the more detail you have to maintain under change. This basic lesson of “no free lunch” is often completely missed in Generative AI systems. The more levels you have in your Intent/Actualisation Toolchain, and the “fatter” your levels are that you expose to the user, then the more burden you and your users will have as change happens.

TLDR: Generating stuff is a burden if the inputs change.

Modalities

One of the problems with Intent/Actualisation Toolchains is that the “phases” can be “modal”. For example, editing the “Initial Intent” might be on a different page to editing the “Detailed Plan” or viewing the running “Code”.

Multiple UX modalities are poison to the usability of Intent/Actualisation Toolchains. They however arise automatically if different teams or different designers are given “ownership” of one area or another in the overall tool. You ship your org chart, you ship your team structure.

The AppDev toolchains like GitHub Spark, Lovable and Firebase Studio have done a remarkable job of making development essentially uni-modal, something we also worked very hard on for Copilot Workspace. Achieving modal unity is not simple, and all the people working on these tools put in a lot of design effort to make it seem natural.

A talk from a designer I worked with, Cole Bemis, on modalities in UX design for AI tooling is here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f3Yrms9r_n4

TLDR: Don’t make your toolchains modal

Spec-driven Programming

The basic mantra of spec-driven programming (e.g. as described in this manifesto ) is that the world of “Code is King” is “breaking down”. What does this mean? My interpretation of this is two-fold

- For the last 30 years, the optimal place to perform most technical work on the Intent/Actualisation Spectrum has been “Code”.

- Because of the rise of Generative AI, it is now becoming possible, and perhaps optimal to perform some technical work further to the left on the Intent/Actualisation Spectrum.

Given the dominance of Code is King, this is a profound shift and has very deep consequences for how software development happens and the toolchains and platforms that support it. For example, my own company, GitHub, is a platform started in the Code is King era. Likewise VSCode is an editor started in the Code is King era. There were times, long in the past, when Code was Not King. For example, there were times when most technical work happened in planning, or specification. There were also times when compilers were treated with suspicion and only assembly code counted as reality/actualization. Things are shifting, which is why I find this chart useful.

The obvious criticism of spec-driven development are:

- Specs are inherently not specific enough, and

- Generation is non-deterministic.

I’ve argued elsewhere that objection (1) is not enough to rule out the whole idea of natural language programming generally – that often “ambiguity” is actually useful generality. I won’t recap that argument here. Argument (2) is however a very major question for Spec-driven development, that is, for those who argue that coherent software development can take place at places such as the “Loose Spec” and “Detailed Spec” points of the Intent/Realization Spectrum. The arguments against are:

- Flickering: The generated solution will flicker and differ in very basic ways on each regeneration/update, even for essentially identical specs.

- Instability: Any change in tool, model, or even the slightest change in the spec causes things to change.

To solve this, four approaches are taken

- Bundle the elements together. For example, Intent/Realisation Toolchains might bundle up the

(spec,code,tool)to form a “pinned” triple that all evolve together. This is the approach taken by pretty much all app-dev toolchains. - Lengthen the actualisation chain. We saw above that SpecKit lengthens the “spec —> plan” hierarchy to “constitution –> spec –> plan –> tasks –> code” . This lengthening is happening to try to allow iteration and change to happen a tthe right level.

- Make the spec unambiguous. Some toolchains encourage making the spec ever-more-detailed to the point that it is entirely unambiguous. This is obviously unworkable. In general spec-driven development should be used in areas where “flickering” is fine and any solution in the generated space is sufficient.

- Detach the spec when the going gets rough. It is going to be common to use spec-driven development as a form of “guided generation”, by generating code then at some point detaching the spec, throwing it away or keeping it as mere docs or LLM guidance.

TLDR: The supremacy of Code is King is being challenged, but the jury is out on where spec-centric programming will be viable

Requirements, Not Specs?

In the toolchains above, it should be noted that the only _true_ inputs are user requirements – user intent, (that is, the “Loose Spec” in some of these diagrams). The “elaboration” to a detailed spec is not essential. It may be entirely artificial.

This means that, in some sense, requirements are all these tools need. If information is _not_ in the requirements, then what role it is serving? Often the Detailed Spec or Plan or Shadow Spec or whatever is nothing but an internal artefact used to stabilise compilation of the user’s requirements. If things are internal, it may be they should never be shown to the user at all.

I’m reminded that Cogna’s Requirements –> App pipeline is purely internal, with nothing but requirements consulting as the interface to the user. This is, I think, a good and interesting decision. From a product perspective, however, it means the very strict decision that the Intent/Actualization Toolchain is _not_ a developer tool. It is not an externally facing tool at all. The internal operation of the tool is entirely invisible. Requirements in, app out. That’s it. No code. No PRDs. No detailed specs.

This choice is not at all obvious for tool developers who long to create a “compiler” or “a tool for developers”. The thought of creating a tool for requirements consultants, or automated requirements gathering – this is not obvious at all. It’s not just low code, or no code, it’s more extreme than that. It’s really “Requirements are all you need“.

TLDR: Maybe your toolchain isn’t a developer tool at all. Not at all.

How many stages of elaboration? It Depends!

The design space covered above includes tools with 1, 2, 3, 4 or even 5 stages in their actualisation. Some bespoke toolchains like IDE-generation in Cogna or Lovable probably use even more internally.

This begs many questions: What’s the “right” amount of Spec for a particular programming problem? What structure should that spec have? Is a Detailed Spec necessary or useful at all?

The honest answer is a difficult one for tool designers: it depends. That is, in many simple cases Specs are of no use whatsoever. In many complex cases they act as incredibly useful anchors and guides for agents and may be sufficiently canonical to allow spec-driven development to be practical.

The idea that sometimes “stages” are useful and sometimes they aren’t hints that ideal tools in this space will be flexible about these things. Chat-based coding agents already are pretty flexible, often flexing between “let me write this out in detail” and “let’s just do it”. Tool designers should be careful not to bake in a fixed, static view of elaboration and actualisation.

To Conclude

To conclude: I’ve introduced my personal mind chart of Intent/Actualisation Toolchains, given some examples, and discussed some of the basics of how change and incrementality is approached in these systems. I’ve described how the 30-year status quo where Code is King is breaking down. Finally I’ve discussed how some of these ideas apply to Spec-driven development toolchains in particular, leading to the potential for new toolchains and methodologies.

TLDR: Have fun out there!

2 thoughts on “Intent, meet Toolchain”